Sometimes, in my role as Guidance Counsellor, I get asked to intervene in situations where several consequences have already been implemented. One such example was a second year “feud” between a boy and a girl who had no dealings with each other in first year and were in the same class for the first time in Second year. Over the first few months, their bickering had escalated to Year Head intervention, detentions and still the teachers were reporting problems in the class. In fact, the whole class atmosphere had been impacted and the class was labelled the problematic one of Second year.

“I felt powerless. I was confused, I couldn’t understand why she was treating me like this. I never spoke to her in First year and when we were put in class together this year she started sniggering and whispering to her friends every time I walked into class for no reason.”

(Boy X)

These were the words of the boy in a preparation conversation before a Restorative Meeting. But they didn’t come easy. In the first round of the questions, I learned he was angry and that he thought his reputation was ruined. He couldn’t get beyond defending himself and making her out to be the ‘bad guy’. He wanted compensation and for the Year Head to call an assembly and tell the whole year he didn’t do ‘it’. At that stage, based on those answers, I was skeptical that there was a readiness for a Restorative Meeting between the two parties.

In my work as an RP practitioner, I know that identifying what feelings reside behind the facts listed are where connection and empathy are built so I delved a little deeper – back to the start of the story rather than this specific incident. I followed the question protocol again and that’s when we started getting somewhere and he made the above revelation.

This boy was very articulate, and I could empathise with the feelings he described. He described the mixed emotions of new beginnings, new classmates, and the added burden of this mysterious quarrel with a girl he didn’t know who just had it in for him. In an attempt to regain power, he began acting in a way that he wasn’t necessarily proud of but couldn’t think of approaching any differently. ‘Investigating’ the incident that landed them in my office wasn’t the priority, giving them clarity and a new path forward were.

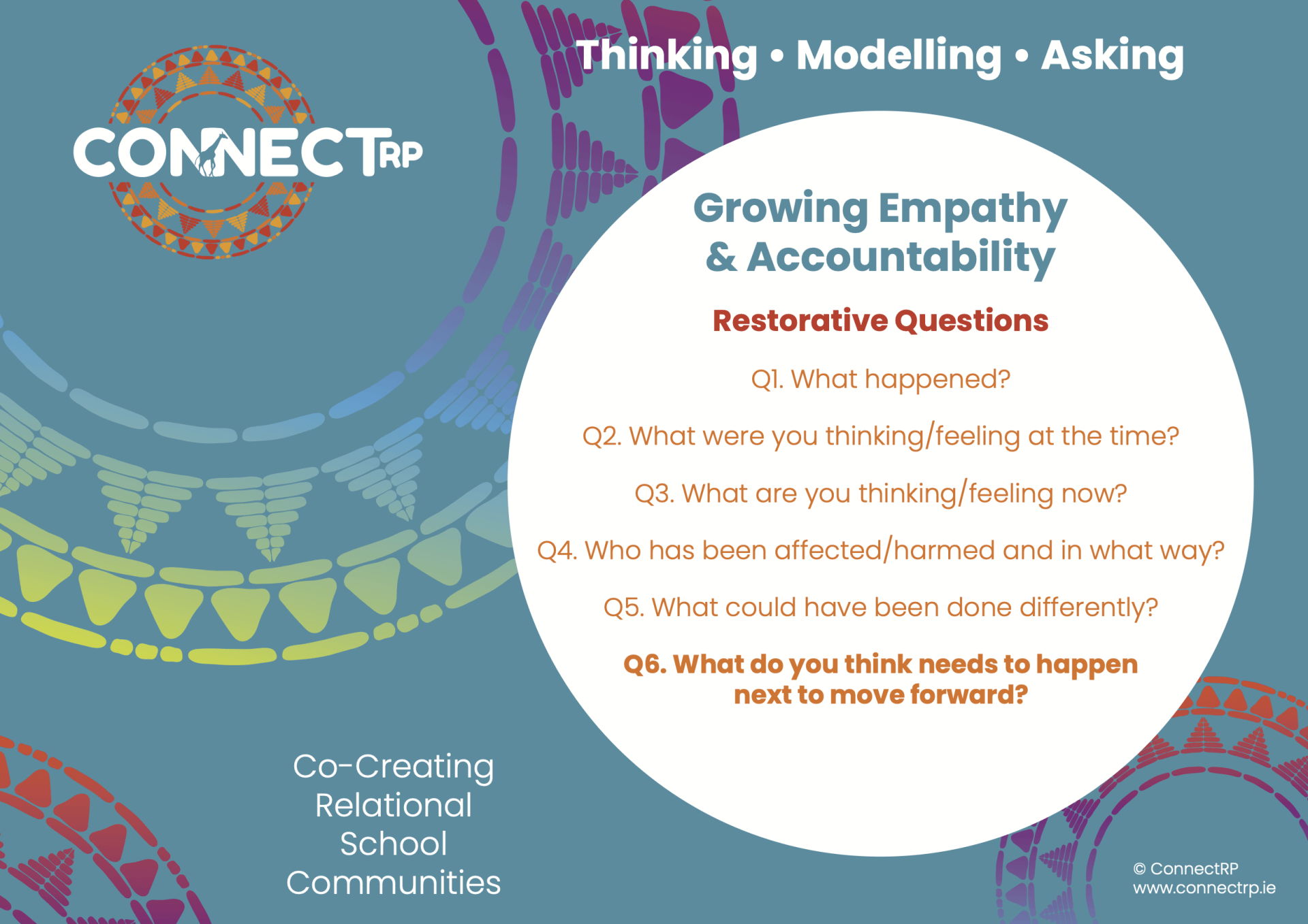

The six questions typically guide my conversation but the more I learn about them, the more nuanced my conversations can be. Michelle calls it the dance - the ability to use these steps to choreograph something unique. I think of the questions as a tool, and much like if you handed me a drill, hammer and saw I couldn’t make you a kitchen cabinet but give me some time and practice and maybe I could learn. The questions are a tool and while their value increases with the skill of the person using them, even at the very beginning they can open amazing conversations. With greater awareness, their true value is revealed:

What happened? - a safe entry point and a non-threatening way to open a conversation. I’ve often found two accounts of an incident can be very similar, sometimes just starting in a different place (which is usually where that person sharing felt like the injured party!)

What were you thinking at the time? - in that moment you were doing the best you could so what was happening for you that made those your best options?

What have you thought about it since? - with a clear head, is anything different for you? How has this impacted you? After the action/behaviour, how are you feeling? Was it worth it?

Who was affected and how? - moving to a bigger picture, developing empathy.

What could have been done differently? - The Game Plan, if you are in the same situation or have the same thoughts, what is a better option? It’s very difficult to come up with a new way of thinking in the moment but a calm reflection can yield an alternative.

What needs to happen next? - to allow you to move on, to heal the hurt, to contribute to the community, to make amends. The words matter less than the intention. Often people say students learn off the answers – focus on the intention of the questions, hold the discomfort of a silence, don’t allow a surface apology to get a student off the hook and out of having to face the reflection brought by questions.

I went through the same process with the girl and then we agreed to all meet together. What he heard from the girl lifted the confusion and allowed him to reflect on some of his actions that contributed to this situation that he wasn’t even aware of.

“In First Year, he called a girl in our year fat. I was confused because she wasn’t fat so there was no reason to start picking on her. It did stop but when we were put in the same class in Second Year I was scared that he would come at me for no reason. I felt scared and powerless, so I got in there first.”

(Girl X)

They both acknowledged that they didn’t want to be responsible for another person feeling as bad as they had been feeling. I wasn’t sure the students knew how to treat each other with respect, even though they both agreed that was what needed to happen next, so we spoke about what it would look like. It was affecting the whole class dynamic so we did some additional work on how they could navigate it if other students got involved. They came up with sentences like:

“I didn’t hear him say that so I’m not going to get involved”

“we’ve spoken and we’ve both agreed not to say mean things to or about each other”.

They both felt these would be helpful if others in the class tried to ‘stir up drama'. In the end, they left with a different understanding of each other and themselves. The atmosphere changed that day because their confusion lifted and they could relate to each other better - the opportunity to grow such empathy is at the heart of restorative conversations and one of the reasons I love the work I get to do!

If you would like to learn more about facilitating such conversations check our our Middle & Aspiring Leaders workshops

here